(Read in preparation for a trip to Spain that has been put on hold, but will one day happen!)

Homage to Catalonia, by George Orwell

I started this to learn something about the Spanish Civil War but soon realized I was at least as interested in Orwell—the human being and the writer. Orwell the human being who went to Spain in 1936 and was so inspired by the fight he saw there against fascism that he joined one of the militias and was wounded (his doctors proclaimed him the luckiest man alive to have survived a bullet through the neck; his rejoinder: “I could not help thinking that it would be even luckier not to be hit at all.”) Orwell the human being, whose conscience dictated that he must tell the truth about the infighting on the Republican side, no matter how little anyone wanted to hear it. And Orwell the writer, with his understated wit and his eye for detail, who shows us so vividly everything from child soldiers whose shouts sound more like the cries of kittens than like war cries, to the coming of spring to the hillsides, where he finds “here and there in the soil … the green beaks of wild crocuses or irises poking through.” Lionel Trilling’s introduction, wherein he proposes that Orwell was a virtuous man, is also an excellent read.

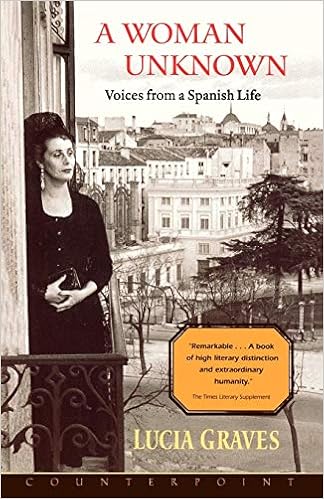

A Woman Unknown, by Lucia Graves

Graves tells the story of growing up straddling two cultures: the daughter of British writer Robert Graves (I, Claudius; Good-Bye to All That), she spent her childhood in a Majorcan village and later married a Catalan and lived for twenty years in Barcelona. In between she went to Oxford and studied literary translation, which became her profession: Graves is the translator of the novels of Carlos Ruiz Zafón into English. As she tells her own life story, beginning with her indoctrination in a Franco-era Catholic school, she weaves in stories of other women’s lives that intersected with hers, among them the village midwife, her family’s housekeeper, and her Latvian-born ballet teacher. Graves shows how the Civil War affected each of these women’s lives, and shows how constricting life could be for women in the Franco era. I particularly liked the glimpses of life in Graves’s mountain village in the late 1940s and early 50s, where the fisherman’s wife would stand outside the town hall on mornings she had fish to sell and blow a conch shell. Everyone heard it, Graves writes, “because those were the days before mechanical noises had invaded their homes, before televisions and telephones closed houses upon themselves, when people’s ears were alert to every sound and could tell what was happening around them.”

-Kirsten G.